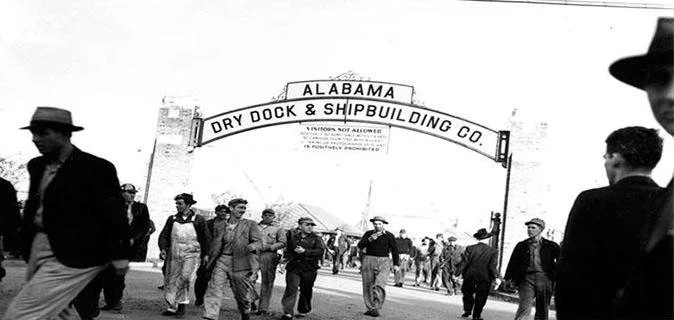

Workers at ADDSCO during a shift change. ADDSCO collection The Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of South Alabama.

A garage on St. Michael Street converted into a dormitory for war workers. Ken Burns “The War - A Deadly Calling” September 23, 2007

Wartime housing for workers at ADDSCO. ADDSCO Collection, the Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of South Alabama

Between 1940 and 1943, over 89,000 individuals migrated to Mobile to take advantage of burgeoning job opportunities in the defense sector. This surge caused the city's population to swell from approximately 78,000 to an estimated 125,000, with the metropolitan area reaching around 260,000 residents. By March 1944, Mobile County's population had grown to 233,000, marking a 64% increase from 1940.

The Alabama Drydock and Shipbuilding Company (ADDSCO) expanded its workforce from 1,000 to nearly 30,000 employees, while Gulf Shipbuilding grew from 240 to 11,600 workers. Brookley Army Air Field also became a significant employer, providing jobs for approximately 17,000 civilians

The rapid population growth led to severe housing shortages. Many newcomers found themselves in overcrowded and substandard living conditions. Boarding houses often required tenants to share beds in shifts, a practice known as "hot bedding." Some individuals resorted to sleeping in parked cars, on park benches, or in makeshift shelters. Trailer parks, hastily constructed by the federal government and private enterprises, became home to thousands of "trailer wives" and their families. Author John Dos Passos noted the stark contrast in living standards, observing that "housekeeping in a trailer with electric light and running water is a dazzling luxury to a woman who's lived all her life in a cabin with half-inch chinks between the splintered boards of the floor."

To address the housing crisis, the Federal Housing Authority initiated several projects in Mobile. Approximately 11,000 residential units were constructed across sixteen housing developments, though only two were designated for Black residents. Notable among these was the D'Iberville Apartments, built in 1943 with FHA-insured financing to provide affordable housing for war workers

The influx of residents overwhelmed Mobile's public services. The U.S. Office of Education deemed the city's schools the worst in the nation due to severe overcrowding, with reports indicating that up to 3,000 children were unable to attend classes. Emergency measures included converting warehouses and other buildings into makeshift classrooms.

The sudden demographic shift also disrupted the city's social fabric. The established aristocracy of Mobile often viewed the newcomers with disdain, leading to tensions between long-time residents and the new workforce. Additionally, the migration of workers to defense jobs created labor shortages in other sectors, notably in agriculture, education, and service industries.

Recognizing the challenges faced by rapidly growing industrial centers, the federal government allocated over $2 billion in bonds in January 1942 to support housing and infrastructure projects in war boom towns like Mobile. These funds facilitated slum clearance initiatives and the construction of additional housing units, including government-provided trailers to accommodate approximately 7,000 workers.

Despite these efforts, the city's infrastructure remained under significant strain throughout the war years. The experiences of Mobile during this period highlight the profound impact of wartime mobilization on American cities, reshaping their demographics, economies, and social landscapes.

Workers Swarm

Men and Women working to repair instruments at Brookley Field. 1. Mary Martha Thomas, Riveting and Rationing in Dixie: Alabama Women and the Second World War 37