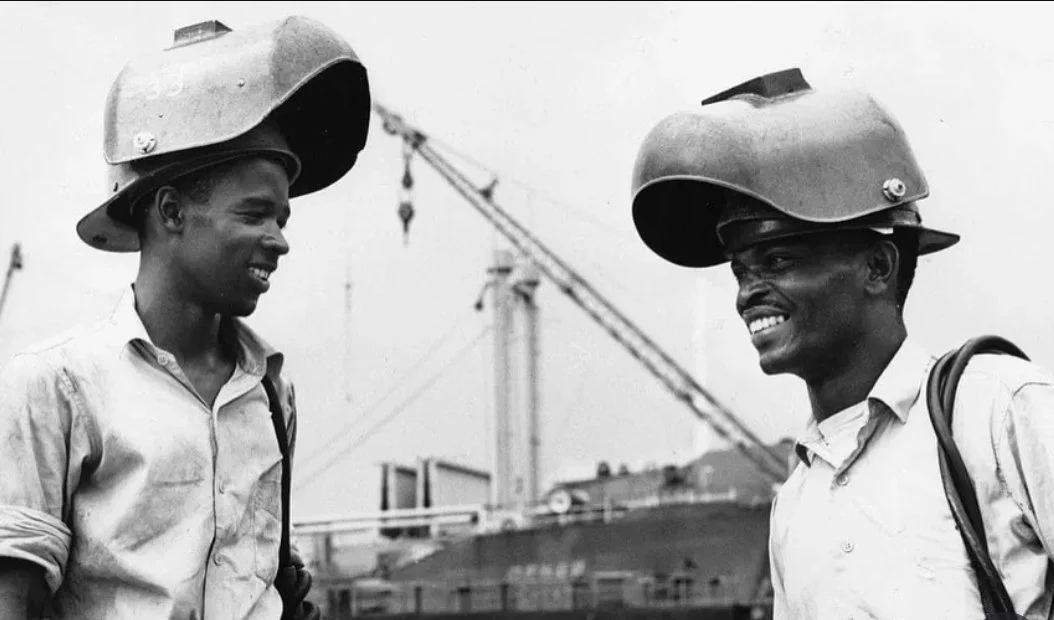

Black welders at ADDSCO circa 1943. Unknown photographer.

War Industry and Civil Rights

World War II brought sweeping changes to the American South, particularly in cities like Mobile, where the defense industry boomed seemingly overnight. For African Americans, the war years offered unprecedented but often temporary access to industrial jobs, as labor shortages opened doors that had long been closed due to racial discrimination.

As the United States ramped up its war production, industries across the nation, including shipyards and aircraft facilities, found themselves in desperate need of workers. In 1941, under pressure from civil rights leaders like A. Philip Randolph, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802, banning discriminatory hiring practices in the defense industry and creating the Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC) to enforce it. Although met with resistance especially from Southern politicians the FEPC helped lay the groundwork for African American workers to demand better treatment and fair hiring.

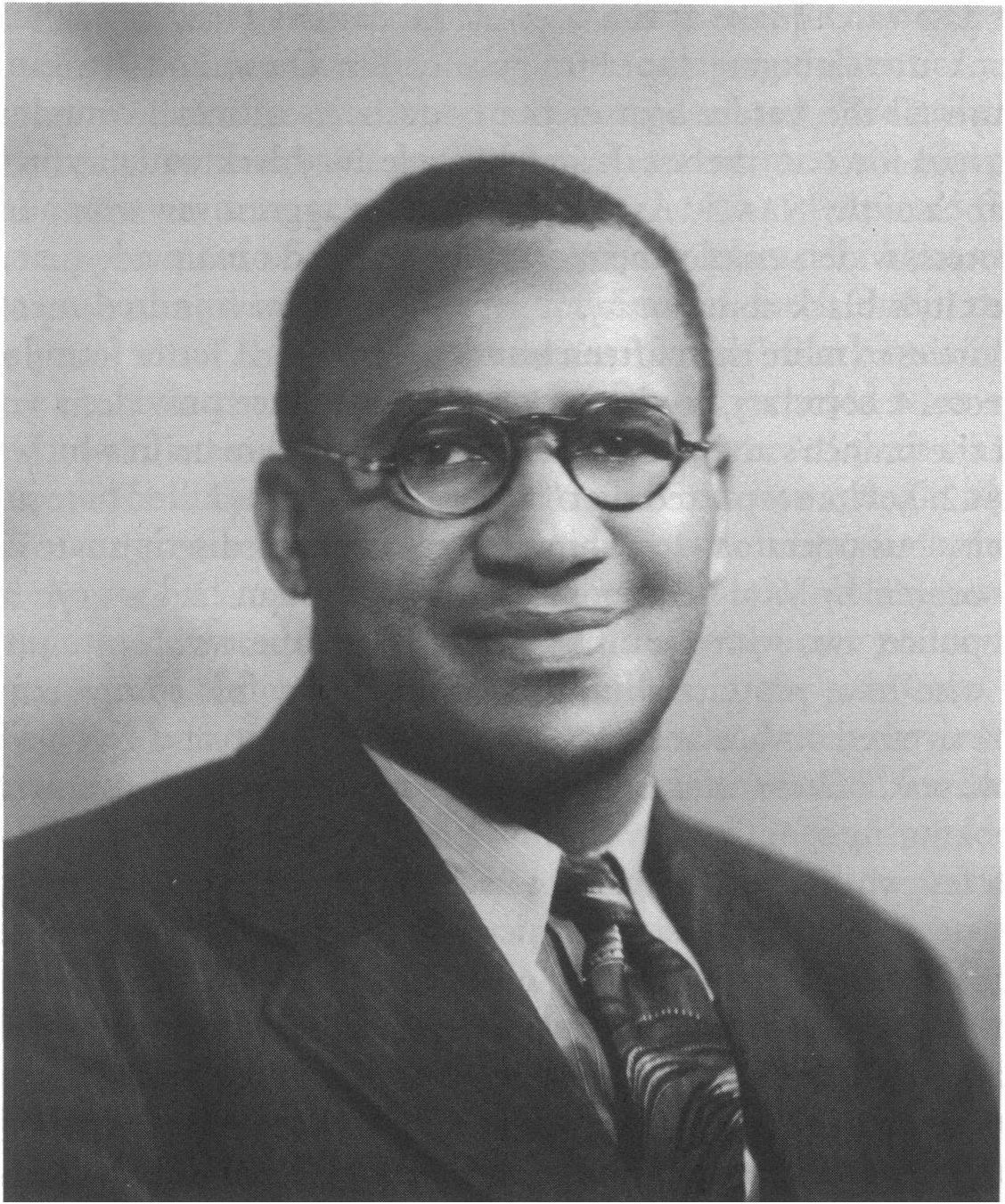

In Mobile, local black leaders such as John LeFlore, head of the NAACP chapter, pushed hard for equal access to war jobs and improvements in public accommodations. LeFlore advocated for better transportation options for Black workers and challenged the segregation of lunch counters and public facilities, pushing Mobile toward a more equitable labor environment—even if only incrementally.

By 1942, Black Alabamians were entering the defense workforce in greater numbers than ever before. At Alabama Drydock and Shipbuilding Company (ADDSCO) one of the region’s largest employers, Black workers were initially relegated to menial or unskilled jobs. But under pressure from the FEPC and the Union of Marine Shipbuilders, the company agreed to train and integrate Black welders into previously all-white crews. This progressive step was not without backlash. In May 1943, tensions boiled over when white workers violently protested the policy, injuring eight Black and one white worker. Though the “melee,” as it was called, did not escalate to the levels of deadly race riots seen in Detroit or Los Angeles, it underscored the fragile racial climate in Mobile.

Despite these challenges, Mobile's African American population grew rapidly during the war. Between 1940 and 1950, the number of Black residents increased from 29,000 to 46,000, as people from across the Deep South poured into the city seeking jobs in shipyards and support industries. Many found employment at Brookley Field, which hired thousands of civilians—many of them Black women—for technical and clerical roles.

While economic opportunity improved for some, racial inequality persisted in the streets and neighborhoods of Mobile. As Mayor Joseph Langan later recalled, the city’s racial climate hardened during the war. In the prewar years, it had not been uncommon for Black and white families to live on the same block. But by the war’s end, social divisions had deepened, and Mobile had become more rigidly segregated and racially intolerant.

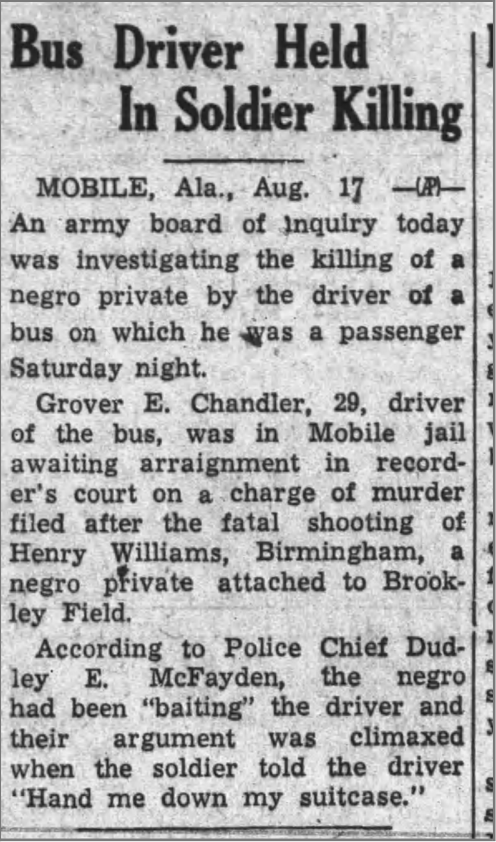

A tragic illustration of this tension was the murder of an African American soldier named Henry Williams, killed while home in uniform. The murder deeply shocked Mobile’s Black community and exposed the contradiction between fighting for democracy abroad and facing injustice at home. Williams’ death became a rallying point, causing a surge in the membership of the local NAACP chapter as well as symbolizing the unfinished fight for racial equality in the very city where many African Americans had labored to support the war effort.

The economic boom of wartime Mobile created opportunities that forever altered the city’s Black working class, setting the stage for postwar civil rights activism. While many gains were rolled back after the war, the experience of labor, resistance, and resilience during World War II left an enduring legacy in Mobile’s African American community.

Copy of EO.8802 which banned workplace discrimination

Mobile Civil Rights activist John L. LeFlore who founded the Mobile chapter of the NAACP and advocated for the rights of the cities many black war workers

Henry Williams in uniform circa 1941

News article detailing the arrest of Grover Chandler who gunned down Williams

News article detailing the murder of Williams

Pittsburg Courier issue detailing the result of the Mobile NAACPs effort to disarm the cities bus drivers in its segregated state.